Elliot Mitchnick discusses the design and construction of the Tsukubai, the traditional place of ritual cleansing in the inner Japanese Tea garden. If you have Japanese enabled on your browser, you will see most terms with their kanji. In addition, most terms have definitions available by holding your mouse over the word. The entire list is available here.

The Tsukubai つくばい

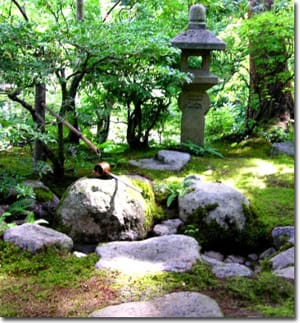

Seattle Urasenke Foundation – Tsukubai photo by Christian Martini

Upon entering the outer tea garden, or Sotoroji, you walk the dewy path of the roji 露地, leading you to the middle gate known as chumon 中門. Now you have passed from the outside world into the separate and pure world of the inner Tea garden, Uchiroji. Continuing on the roji, you will come to a special place called tsukubai つくばい. Here, a stone water basin for purification is surrounded by other stones assigned specific purposes, most often based on established Tea ceremony procedures. In the Tea garden, the tsukubai is near the entrance to the tearoom and not in direct view from the tearoom. It is somewhat hidden by carefully placed shrubs and trees.

According to A CHANOYU VOCABULARY, the term “tsukubai” originates from the Japanese verb “tsukubau”, meaning to squat or crouch, and refers to the fact that one must crouch or bend down to use the basin. This is the form we will discuss here. In some cases, especially in temples and homes, only the stone basin called chozubachi 手水鉢 is present, while temple gardens with tea rooms usually have the more traditional tsukubai arrangements. In both cases, the basin itself is the same and the ideal of purifying oneself remains, but the aesthetics of the Way of Tea brings a more refined use and design.

At first, only three stones were used in the tsukubai arrangement: the chozubachi we have already introduced, the mae-ishi 前石 aproach stone where one stands, and the hikiae-ishi supporting stone. Later, the candlestick stone; teshoku-ishi 手燭石, was added on the right side, and to the left is yuoke-ishi 湯桶石, a stone to support a water bucket. This arrangement evolved to include a drain area in the center framed by these four stones collectively referred to as yaku-ishi 役石 .

The term yaku-ishi literally translates as “role stones”, and are included for practical reasons. Therefore in the roji garden, yaku-ishi are the chozubachi for cleansing, along with the teshoku-ishi where the candle holder is placed during an evening tea, the yuoke-ishi, stone for placing the bucket for warm water in cold seasons, and the mae-ishi, stone used to stand or crouch in front of the chozubachi. A stone lantern ishidoro 石灯籠 is usually placed near the tsukubai to provide light during an evening tea. The ishidoro is not necessary, but is a beautiful addition to the tsukubai. More on ishidoro can be found in the section on Stone Lanterns.

It is not possible to thoroughly address stone selection for the tsukubai in this short article, but there are a few important points to remember. Sedimentary stones are often soft and easily chip, crack or flake and should be avoided. All but the hardest limestone should be avoided, as should cracked stones, soft stones and stones that are pointed, or too oddly shaped, no matter how beautiful. These odd shaped stones can be placed in an area outside of the roji where they can be appreciated for their specific beauty. The tsukubai requires simple stones to develop the aesthetics of this place of purification. These are some things to strive for when looking for stones. However, if you can only find the lesser types of stone, sometimes you must make do with what is available within your budget.

It is not possible to thoroughly address stone selection for the tsukubai in this short article, but there are a few important points to remember. Sedimentary stones are often soft and easily chip, crack or flake and should be avoided. All but the hardest limestone should be avoided, as should cracked stones, soft stones and stones that are pointed, or too oddly shaped, no matter how beautiful. These odd shaped stones can be placed in an area outside of the roji where they can be appreciated for their specific beauty. The tsukubai requires simple stones to develop the aesthetics of this place of purification. These are some things to strive for when looking for stones. However, if you can only find the lesser types of stone, sometimes you must make do with what is available within your budget.

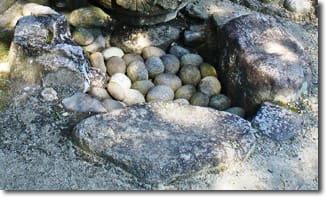

The “Role Stones” – Photo by Lee Schneller Sligh

Then what stones do you need for your tsukubai and how do you pick them? We will start with the chozubachi. Many are available at garden centers made of stone or cast cement. Most of these are taken from a Japanese model, but are not really best for a tea setting. Some very beautiful and ornate chozubachi are seen in Japan at temples and if you are lucky enough to have one, use it. Most of the garden center types can be used when selection is limited. The best chozubachi is a simple stone with a carved holding area for water. Look for a hard stone with a smooth imperfect face without a shiny finish. A slightly irregular surface is a definite plus. Although the ideal color is grey, stones with brown or other tones can be used. The stone should look hard, not muddy or powdery like some soft stones. With these points in mind, you will likely recognize a good stone when you see it. You may wish to visit a stone mason or a good stone yard to get help in your search for a “perfect” chozubachi stone.

The mae-ishi should be a low flat stone, more than 3or 4 inches thick for stability, and large enough for a guest to place both feet comfortably. The Yuoke-ishi should be taller than the mae-ishi with a flat-top to hold a teoke 手桶 wooden bucket without fear of it falling off. The teshoku-ishi should also be a taller flat stone that can hold the teshoku 手燭, which is about 12’’ long and 5” wide. When used , the teshoku will have a lit candle and you do not want to have it fall on to the surrounding plants. Both stones should be about 12” tall, but taller stones can be buried deeper. If you have a teoke and teshoku, bring them to make sure the stones will be the right size.

Drain area stones – Photo by Lee Schneller Sligh

The stones for the drain area should be river stones (not too shiny) or other round stones in the 2 to 4 inch size, depending on the drain area and surrounding stones. Other stones that surround and contain the drain area stones should be selected using the same criteria you used for all the stones for the tsukubai arrangement.

Once all the stones are placed and you are happy with the placement, you can think about the planting around the tsukubai. Remember that when crouching on the mae-ishi, you should be able to easily reach the tsukubai hishaku ( wooden ladle ) that sits across the water basin. If it is difficult for a smaller person to use, consider moving the mae-ishi closer to the chozubachi and readjusting the other side stones.

For planting, use foliage rich plants with rich green leaves. You do not want lots of colorful flowers in the roji and around the tsukubai. Local plants are best. Try to avoid rare plants as well as variegated plants. Remember that tea guests will be wearing valuable kimono, so keep your plantings away from stones around the mae-ishi. In this way, if it is raining and the plants are wet, they will be away from the kimono and prevent stains. Your guests will be most appreciative.

Tsukubai in private garden – San Antonio, Texas

When planting the tsukubai area, a light touch is best. Plant selection is dependent on the climate in your area, and the location and light conditions around the tsukubai. Most often, the tsukubai area is shady and moist, so plants that thrive under these conditions would be appropriate. Typically, green-leaved ferns, and other low plants make good plants near the tsukubai. Taller plants in complimenting tones of green can be used to the rear and behind, with a graceful, arching plant such as Japanese maple for the “roof” of the tsukubai area. Keep in mind how the area will look in all the seasons it will be in use.

The drawings in this article offer general details on the building of the tsukubai. These are based on a number of sources and the tsukubai at Toinseki, the Urasenke “training” tea room. This format should be considered a template and one’s own vision should be combined with the template to build a tasteful tsukubai. Good luck!

Elliot Mitchnick holds the tea license rank of Junkyoju (Associate Professorship) of Urasenke School of Tea.. His tea name (chamei) is Soei. Sketches and editing by Don Pylant.

THIS WORK IS PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT AND/OR OTHER APPLICABLE LAW. ANY USE OF THE WORK OTHER THAN AS AUTHORIZED UNDER THIS LICENSE OR COPYRIGHT LAW IS PROHIBITED. CONTACT [email protected].