A JAPANESE GARDEN HANDBOOK

PART ONE: DESIGN & CRAFTChapter 6: The Contemplation Garden

In this Chapter…

- Gardens for the Mind

- The Painter’s Eye

Gardens for the Mind

During the Muromachi period (1338-1568), due mainly to the influence of Zen Buddhism, a new style of garden arose that was not intended to be entered physically. The contemplation or meditation garden was a spiritual sanctuary, a three-dimensional landscape art designed to be viewed like a painting from a seated position in a room or on the veranda of a nearby building. For this reason, they are sometimes collectively termed kanshō-niwa (観賞庭園 “view-praise or admiration gardens”; kanshō-shiki-teien 観賞式庭園 “view-form-gardens”) or zakan-shiki-teien (座観式庭園 “seated-view-form gardens”). If the garden design centers on a pond, the preferred term is chisen-kanshō-shiki-teien (池泉観賞式庭園 “pond-spring view-form garden”). In all cases, the essential idea is a garden for the spirit, designed to be toured mentally with the eye rather than with the legs. Marc Keane captures something of the surreal ambiance of these contemplation gardens in The Art of Setting Stones: “I sit on the veranda to be closer to [the stones] the way one will sit at the edge of the ocean, not needing to enter to be refreshed.” The illimitable has been compressed within the narrow confines of the physically small garden space.

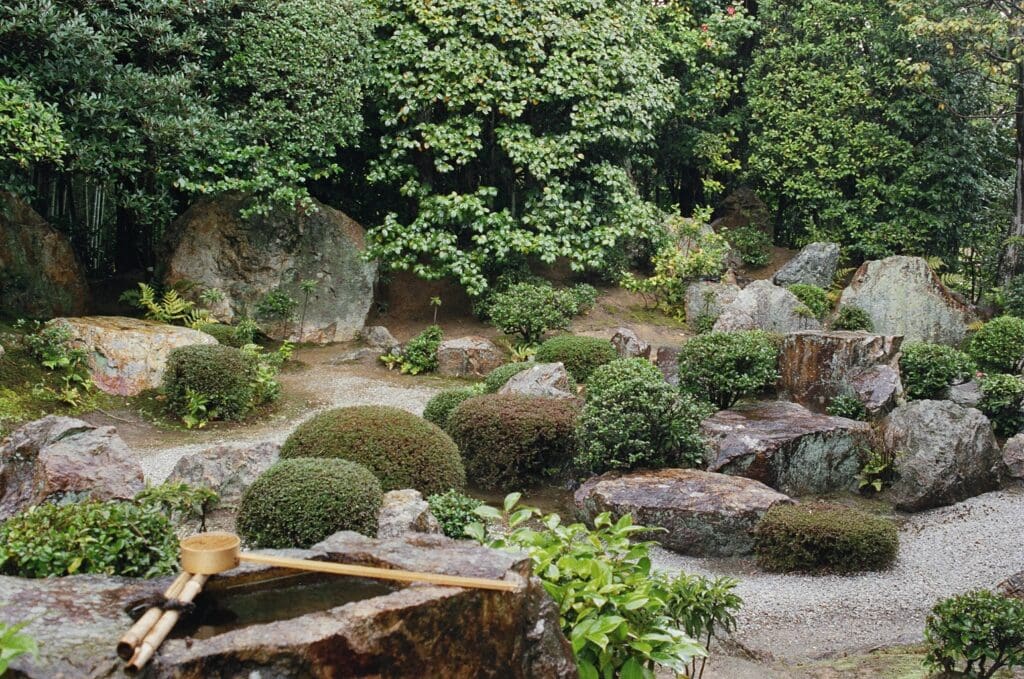

Part of the contemplation garden at Daishin-in, Kyoto

Since the Heian period (794-1185), a gradual shift away from the austere grandeur of shinden-zukuri (寝殿造り “shinden architecture”) led to the development of the more condensed austerity of shoin-zukuri (書院造り “shoin architecture”), and consequently to the adoption and perfection of contemplation gardens. First, the size of the available space for gardens was greatly reduced, and secondly, the use of shōji (障子, paper-covered screens) and tatami (畳, reed mats) in place of cumbersome shitomi (蔀, heavy wooden shutters) and uncomfortable hardwood flooring encouraged viewing from within buildings. Since many contemplation gardens were attached to temple buildings, they tended to follow the dry landscape design by default (karesansui 枯山水). The most famous of such gardens is, of course, the dry landscape at Ryōan-ji, which may have been completed as early as 1499.

A trend developed during the Kamakura period (1185-1333) for creating larger, split-level contemplation gardens. In the jōge-nidan-shiki-teien (上下二段式庭園 “upper-lower, two step garden”), the designer splits the garden into two visual planes, the lower usually featuring a small pond, and the upper centering on an artificial hill and plantings. As with traditional contemplation gardens, both sections are designed to be viewed from the vantage point of the buildings. The jōge-nidan-shiki-teien reached its zenith in the Muromachi period, with famous examples at Nanzen-in, Nanzen-ji and Shōren-in. As with most terms for garden styles, those used for contemplation gardens were also coined by modern historians.

The Painter’s Eye

The term hokusō-sansuiga-shiki-teien (北宋山水画式庭園 “early Sung dynasty mountains-and-water-paintings-form gardens”; suiboku-sansuiga-shiki-teien 水墨山水画式庭園) “water-ink mountains-and-water-paintings-form gardens”) refers to contemplation gardens inspired by and created in the style of the landscape paintings of the early Sung dynasty of China (959-1279). Chinese landscape paintings were extremely popular in Japan, particularly around the middle of the Muromachi period (1338-1568), when garden masters began to consciously imitate their dramatic verticality, sharp delineation and monochromatic palette in the design and construction of their gardens.

The “painterly” garden, Taizō-in, Kyoto

Loraine Kuck coined the term “painted garden” to capture this dominant artistic influence on Muromachi-period dry landscape design and rock configurations. Typical examples include Jōei-ji, Mampuku-ji and Ikō-ji, all accredited to the famous Zen painter, Sesshū Tōyō (雪州等揚, 雪舟等揚 c.1420-1506), and Daisen-in, either the work of Kogaku Sōkō (古嶽宗亘 1464/5-1548) or Sōami (相阿弥 c.1455-1525), or both. In particular, Kuck draws attention to the similarity of the angular, rectilinear brushstrokes in Sesshū’s paintings and the flat-topped, angular rocks used in Muromachi rock formations: “[T]he interrelationship of the gardens to painted landscape pictures – of stonework to brushwork – came full circle when the strokes of the painter were used to recreate the essentials of natural rocks, and actual rocks were used in gardens to suggest the brushstrokes of the painter.”

A view to admire, Shisen-dō, Kyoto

Günter Nitschke reinforces the idea that the term “painted garden” refers specifically to those gardens that can only be understood “with reference to landscape painting and which subject the external forms of nature to a similarly high degree of abstraction.”

Scrolling through Tenryū-ji, Kyoto

David Slawson, on the other hand, prefers the term “scroll garden”, and cites the fourteenth-century landscape garden centered on the pond to the west of the main hall at Tenryū-ji as a classic example. A scroll garden, he adds, was designed to be viewed primarily “like a painting seen from several vantage points centering around a principal one.” Herein lies the fundamental difference between the scroll garden and the stroll garden: “[A] scroll garden is revealed all at once in a single frame, whereas a stroll garden unfolds in a sequence of many frames… When a site is fully open to view from a gallery, a wall of windows, or other extensive viewing area, the scroll garden naturally takes precedence…” In other words, the architecture of adjacent buildings forms the frame through which the garden is perceived.

Bibliographical Notes

Three places to start:

- Kuck, L. (1968; 1984). The world of the Japanese garden: From Chinese origins to modern landscape art. New York & Tokyo: Walker/Weatherhill.

- Mansfield, M. (2009). Japanese stone gardens: Origins, meaning, form. Foreword by D. Richie. Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing.

- Slawson, D. A. (1991). The art we see: Sensory effects. In Secret teachings in the art of Japanese gardens: Design principles, aesthetic values. Tokyo & New York: Kodansha International Ltd.

Just as the Japanese tea ceremony and the ikebana flower arrangement make frugality a virtue… Cited in Mansfield, M. (2009); p. 9.

Marc Keane captures something of the surreal ambiance… Keane, M. P. (2002). The art of setting stones & other writings from the Japanese garden. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press; p. 115.

We entered the stone archway that led to the garden… Booth, Michael (2010). Sushi and Beyond: What the Japanese Know about Cooking. London: Vintage Books; p. 145.

Loraine Kuck coined the term “painted garden”… The term appears first in Kuck, L. (1968; 1984). The world of the Japanese garden: From Chinese origins to modern landscape art. New York & Tokyo: Walker/Weatherhill.

[T]he interrelationship of the gardens to painted landscape pictures… Kuck, L. (1968; 1984); p. 153.

Günter Nitschke reinforces the idea… Nitschke, G. (1993). Japanese gardens: Right angle and natural form. Köln: Benedikt Taschen; p. 88.

A scroll garden, he adds, was designed to be viewed… Slawson, D. A. (1991). The art we see: Sensory effects. In Secret teachings in the art of Japanese gardens: Design principles, aesthetic values. Tokyo & New York: Kodansha International Ltd.; p. 81.

“[A] scroll garden is revealed all at once in a single frame…” Slawson, D. A. (1991); p. 81.

THIS WORK IS PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT AND/OR OTHER APPLICABLE LAW. ANY USE OF THE WORK OTHER THAN AS AUTHORIZED UNDER THIS LICENSE OR COPYRIGHT LAW IS PROHIBITED. CONTACT [email protected].

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Setting aside a Space

Surrounded by Nature; Taming Nature; On Speaking Terms

Chapter 2: Categorizing Japanese Gardens

“Japanese” Gardens; Categories and Schemas; Making a List and Checking It Twice

Chapter 3: The Heian Estate Garden

An Austere Grandeur; The Southern Courtyard; The Boating Pond; Dragon Boats and Rooster Tales; Pavilions and Platforms

Chapter 4: The Paradise Garden

Paradise at Hand; The Easy Way; This Place Is the Lotus Land; The End of the World

Chapter 5: The Dry Landscape Garden

An Extraordinary Vision; Origins and the Zen of Sterility; Going Mental; Less Is More; The Most Difficult Part; Cubs and a Querulous River; At a Rakish Angle; Water, Water Everywhere…

Chapter 6: The Contemplation Garden

Gardens for the Mind; The Painter’s Eye

Chapter 7: The Tea Garden

The Taking of Tea; Brewing History; The PhDs of Tea; Along the Dewy Path; Leaving the World Behind; Entering the Sanctuary; A Mountain Hut; Room for Tea; “Tea” Plants

Chapter 8: The Courtyard Garden

All Boxed In; Nature in a Tray; Natural Reduction; Living Landscapes

Chapter 9: The Stroll Garden

A Network of Paths; Friendship Gardens; Amalgamation; Mountains and Sea; Piling Up Sand

Chapter 10: The Hermitage Garden

Retiring from the World’s Stage; Illusions of Seclusion

Chapter 11: Nature: Essence and Quintessence

Nature, Naturally; Recreating Nature; Heian Naturalness; Garden Styles; Habitat Motifs

Chapter 12: Aesthetics

At a Loss for Words…; Heian Sensibilities; Far from Idle; Zen Elegance; Stillness; Tea and Flowers; The Beauty of Paucity; The Cult of Simplicity; Ranking Things; Town Tastes; Illusions of Grandeur

Chapter 13: Perspectives

Space; Dimension; Tension; Asymmetry; Perspective; Landscape Architecture

Chapter 14: Designing Men

Past Masters; Talent from Overseas: Kanroku and Michinoko no Takumi; Heian Classicists: En’en-Ajari and Tachibana no Toshitsuna; Zen Men: Musō Sōseki and Kogaku Sōkō; Tea Drinkers: Sen no Rikkyū and Furuta Oribe; Imperfecting Perfection; Les Très “Amis”: Nōami, Geiami, and Sōami; Arbiters of Taste; The Art of Gardening: Sesshū Tōyō and Kobori Enshū; Modern Masters: Ogawa Jihei and Shigemori Mirei

Chapter 15: The Men Who Moil

Earth Movers; Stone Standers; River Folk; Graffiti Artists; The Pros; Tools of the Trade

Chapter 16: Preserving the Craft

Passage and Preservation; Follow the Tune; The Classic; Medieval Manuscripts; Tokugawa Tomes; Modern Manuals